All Saints Episcopal Church, Portland, Oregon

Sermon

Sermon

Sermon

Syllabus

Sermon

Sermon

Sermon

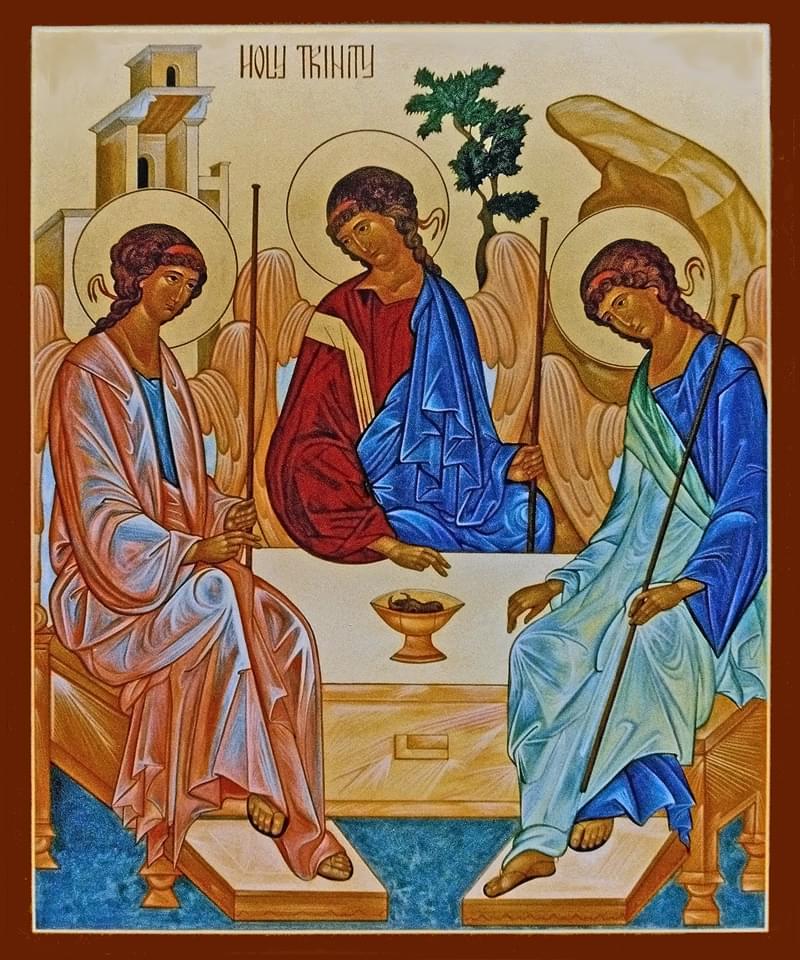

'Holy Trinity' ('The Hospitality of Abraham') written by a Nun of New Skete.

This icon is traditionally entitled “The Hospitality of Abraham.” It depicts the visit of three angels to Abraham and Sarah. Abraham was resting in the heat of the day, likely recovering from his recent covenant with God which resulted in the circumcision of all male members of his household. Upon the arrival of “The Lord,” says the text, Abraham and Sarah immediately welcome their three guests, wash their feet, and provide them with fresh bread, meat, curds and milk. These mysterious guests confirm the covenantal promise that Sarah will bear a son, their descendants will be as numerous as the stars.

This passage, early in the long story of salvation, has long been interpreted as a visitation of three angels who are representatives of ‘The Lord’, the Holy One of Israel. Christians, looking back at Scripture in light of their experience of God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, have seen in this passage an indication of the Trinitarian nature of God. They interpret this passage as typological, and ancient prefiguring of something made more clear much later. It is not that there are simply three visitors which creates this connection, but because of the hospitality given and received, a hospitality which gives us a window into God’s very self.

Look again at the icon. Take it out, hold it in front of you, look closely. Each figure is the same size, each figure holds a rod indicating shared authority. Each wear blue symbolizing divinity, though the central Christ figure wears red as well, the color of humanity. These figures are without clear sex, distinct from one another, yet similar in look and demeanor.

Follow for a moment their gazes and the tilt of their heads. It forms a circle flowing from one to the other, symbolizing their unity of will but distinction of persons. It is a visual depiction of perichoresis. The first part of the word, peri, means “around.” The second is a root from which we get our word ‘choreography.’ This is an image of a divine dance, a movement of perpetual and reciprocal motion, where each person permeates the place, the space of the other. Think for a moment of line dances, where each person holds the hand of the person next to them, following in their footsteps , perhaps with the same pattern, perhaps spinning in a moment of exuberant creativity, but always moving together in a circle which winds its way around the room. This vision of a dance is an ancient, though hardly exclusive, image of one God in three persons, perfectly united in will, distinct and unique in persons, moving together in joyful love.

Look again at the image: take your finger and trace the circle between the faces of each. When your finger moves directly between the figures on either side, the circle distorts a bit. The line between left and right is no longer curved, the circle flattens. This is hardly a circle, barely even and oval.

Now, look again, but this time, imagine yourself in front of a life-size version of this icon, sitting at the table opposite the central figure. Draw the circle again, including yourself. This time, the circle is full, complete.

This is not an accident, some artistic conceit. Rather, icons are written so as to draw us in, to invite us into its activity. Our presence, our participation at this table is required if the circle is to be complete. This theological point lies at the heart of the Christian understanding of God: we experience God as the Holy One whose trinitarian life together, a life which we see but hardly understand, is the way in which God is present to us, and the way in which we are drawn into relationship with the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit.

Isaiah, who catches a glimpse of the awesome holiness of God in the clouds of temple incense, a holiness from which even God’s messengers the angelic seraphim hide themselves, is terrified because he understands that he is among those who have forgotten God. In a scorching moment, he is reminded that God will be remembered, and eagerly volunteers to be sent out to speak God’s reminder. As a prophet, Isaiah cries out the judgment of God, which for us is so easily associated with a wrath that burns away sin, uncleanliness. But remember, Hebrew prophets do two things without fail: they point out our lack of justice and mercy towards those without privilege and security, which of course, makes their listeners uncomfortable and angry, since who likes to have their privilege and power exposed for what it is. But then they extend God’s constant invitation to live as God lives among us, with justice and mercy. What God desires, evident in the persistent pursuit of God, ever seeking his forgetful and unfaithful lover, is to draw us into the dance, to remind us that we are a part of God’s life, that we are called to dance these steps with God the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit.

This is no abstract and fanciful dance, like faeries in some Shakespearean wood. Look again at the icon: the three figure are seated around a table set with food. As angelic messengers they accept the hospitality of Abraham and Sarah. As an image of the Trinity, they invite us to join them at the table, feasting with them. This table is clearly eucharistic, a chalice holds a sacrificial lamb. This is what we do when we gather together and share the eucharist, we receive the hospitality of God. Paul reminds us that we are welcomed not as slaves or even servants, but as daughters and sons to whom, as we were reminded at Pentecost last week, God grants dreams and visions through the coming of the Holy Spirit.

This Spirit is the one who comes along side us, comforts us, advocates for us, birthing us as John tells us, not ‘again’ but ‘from above.’ We, anyone upon whom the restless Spirit descends, are birthed, as an ancient Syriac baptismal prayer says, from “the womb of the Father.” The imitable Julian of Norwich (whose words we will soon hear) reminds us that we are knit together in God the Father, remade and restored in God our Mother.

Our celebration of the Trinity today is not a celebration of seemingly abstract creedal statements. Rather, the Creed is the result of carefully, thoughtfully, daring to speak of the awesome holiness of God who persistently invites us into the divine dance which is the life for which we are made, to which we are called.

We are made in the image of this God, who dances, births, knits, remakes, restores, who burns and blows where she will, all in order that we might be saved, that we might live as we are made to live. Salvation here is not from a wrathful God, but an invitation into being like God, to enter into a life of constant, joyful, dynamic hospitality. Being like God is to take God’s hospitality, and to be God’s hospitality.

The word ‘hospitality’ sounds so pleasant, so very nice, perhaps even a bit trite. But I suspect that every one of us can readily recall a dinner where our inclination for hospitality was stretched. Think of holidays with family or friends where the pleasant camaraderie familiar faces erupted into awkwardness, fear or anger in the face of unexpected, unpleasant, or even downright objectionable differences. Some of us may wisely anticipate such unpleasantness, and hatch an escape plan with our significant other, complete with eyebrow wiggles and suddenly recalled early morning appointments allowing for our immediate departure. We all have moments where we wished to be anywhere but here, with these people, or where we knew we were unwelcome to even darken the doorstep. It is much more comfortable to live and eat amongst our own, and we are quick to punish, ostracize or even kill those who dare to disrupt our smoothly flowing private dance. The truth is, this hospitable image of God is often not what we are actually like.

Welcoming the other, especially those that are already unwelcome, causes suffering. Paul and John do not separate the life of Jesus from suffering with Jesus. Lives of loved ones are disrupted, our neighbors resent the noise and dirt. Our friends, our neighbors, sometimes we ourselves become angry, cruel, and violent. To restore peace and quiet, we cast out, or perhaps we are cast out. We reject the hospitality of others, we deny hospitality to others.

In a world where justice seems only for the strong, and judgment is too often condemnation rather restoration, there may be no greater witness to the Trinitarian nature of God than to be a people who are hospitable. To be those folk who welcome one another as God welcomes us, welcoming friends and foes, strangers and the strange, as if they are themselves divine visitors born of the same womb, caught up by the same wind, brothers and sisters invited to dance and eat at God’s table.